I'm a bit late to the party, but I was just linked Anthony Moser's poetic and impassioned evisceration of LLMs today and I think anyone who hasn't yet read it should do so. I cosign it as an articulation not just of my position on the subject, but of my emotional stance towards it as well. The techno-cultural nexus that we have recently taken to calling "artificial intelligence" is deeply corrosive, and we must not tolerate it. We must not give it air to breathe. When this all falls to an ignominious end, we must dance on its grave that it may never rise again.

I've assumed for a while that gamers would have mild distaste for genAI material, in the same way that they have distaste for asset store assets and, for some reason, the Unity engine. It turns out that I was wrong - they hate it a lot more than either of those things.

I saw Liz England posted about a market research survey from a reliable vendor, Quantic Foundry, which showed that audiences genuinely loathe the technology. Unsurprisingly, players who care more about story hate it even more than the rest of them. Less than 8% of gamers have any positive feelings toward it at all.

62.7% of the survey respondents have very negative feelings about it. Over 85% of all the respondents had at least some negative feelings about it.

This is wild as hell. GenAI boosters are very common on Reddit, Bluesky, and other platforms where people speculate about What Gamers Want and what the future of game development will be like. As long as these survey numbers hold, I'm going to dismiss that kind of boosterism out of hand, and you should, too. There's no reason to assume that this tech will be the norm going forward for game art, audio, or story. The people who insist the audience will prefer it have no idea what they're talking about.

Within moments of opening OpenAI’s new AI slop app Sora, I am watching Pikachu steal Poké Balls from a CVS. Then I am watching SpongeBob-as-Hitler give a speech about the “scourge of fish ruining Bikini Bottom.” Then I am watching a title screen for a Nintendo 64 game called “Mario’s Schizophrenia.” I swipe and I swipe and I swipe. Video after video shows Pikachu and South Park’s Cartman doing ASMR; a pixel-perfect scene from the Simpsons that doesn’t actually exist; a fake version of Star Wars, Jurassic Park, or La La Land; Rick and Morty in Minecraft; Rick and Morty in Breath of the Wild; Rick and Morty talking about Sora; Toad from the Mario universe deadlifting; Michael Jackson dancing in a room that seems vaguely Russian; Charizard signing the Declaration of Independence, and Mario and Goku shaking hands. You get the picture.

Sora 2 is the new video generation app/TikTok clone from OpenAI. As AI video generators go, it is immediately impressive in that it is slightly better than the video generators that came before it, just as every AI generator has been slightly better than the one that preceded it. From the get go, the app lets you insert yourself into its AI creations by saying three numbers and filming a short video of yourself looking at the camera, looking left, looking right, looking up, and looking down. It is, as Garbage Day just described it, a “slightly better looking AI slop feed,” which I think is basically correct. Whenever a new tool like this launches, the thing that journalists and users do is probe the guardrails, which is how you get viral images of SpongeBob doing 9/11.

The difference with Sora 2, I think, is that OpenAI, like X’s Grok, has completely given up any pretense that this is anything other than a machine that is trained on other people’s work that it did not pay for, and that can easily recreate that work. I recall a time when Nintendo and the Pokémon Company sued a broke fan for throwing an “unofficial Pokémon” party with free entry at a bar in Seattle, then demanded that fan pay them $5,400 for the poster he used to advertise it. This was the poster:

With the release of Sora 2 it is maddening to remember all of the completely insane copyright lawsuits I’ve written about over the years—some successful, some thrown out, some settled—in which powerful companies like Nintendo, Disney, and Viacom sued powerless people who were often their own fans for minor infractions or use of copyrighted characters that would almost certainly be fair use.

No real consequences of any sort have thus far come for OpenAI, and the company now seems completely disinterested in pretending that it did not train its tools on endless reams of copyrighted material. It is also, of course, tacitly encouraging people to pollute both its app and the broader internet with slop. Nintendo and Disney do not really seem to care that it is now easier than ever to make Elsa and Pikachu have sex or whatever, and that much of our social media ecosystem is now filled with things of that nature. Instagram, YouTube, and to a slightly lesser extent TikTok are already filled with AI slop of anything you could possibly imagine.And now OpenAI has cut out the extra step that required people to download and reupload their videos to social media and has launched its own slop feed, which is, at least for me, only slightly different than what I see daily on my Instagram feed.

The main immediate use of Sora so far appears to be to allow people to generate brainrot of major beloved copyrighted characters, to say nothing of the millions of articles, blogs, books, images, videos, photos, and pieces of art that OpenAI has scraped from people far less powerful than, say, Nintendo. As a reward for this wide scale theft, OpenAI gets a $500 billion valuation. And we get a tool that makes it even easier to flood the internet with slightly better looking bullshit at the low, low cost of nearly all of the intellectual property ever created by our species, the general concept of the nature of truth, the devaluation of art through an endless flooding of the zone, and the knock-on environmental, energy, and negative labor costs of this entire endeavor.

Landlords are using a service that logs into a potential renter’s employer systems and scrapes their paystubs and other information en masse, potentially in violation of U.S. hacking laws, according to screenshots of the tool shared with 404 Media.

The screenshots highlight the intrusive methods some landlords use when screening potential tenants, taking information they may not need, or legally be entitled to, to assess a renter.

“This is a statewide consumer-finance abuse that forces renters to surrender payroll and bank logins or face homelessness,” one renter who was forced to use the tool and who saw it taking more data than was necessary for their apartment application told 404 Media. 404 Media granted the person anonymity to protect them from retaliation from their landlord or the services used.

“I am livid,” they added.

The person said earlier this year they were verifying their income in order to start a lease at an apartment complex in Atlanta. The apartment complex used a tenant screening service called ApproveShield, the person said. The landlord required 60 days of pay history, or four pay stubs, the person said.

ApproveShield is in-part powered by a tool called Argyle, which verifies peoples’ income. It does this by having people log into their corporate employer HR services, such as Workday, and scraping information stored within. I’ve covered Argyle before, when I found it was linked to a wave of suspicious emails that offered people cash for their workplace login credentials.

The renter said ApproveShield’s Argyle-powered widget asked them to log into their employer’s Workday. That's when they noticed something unusual.

“Argyle hijacked my live Workday session, stayed hidden from view, and downloaded every pay stub plus all W-4s back to 2024, each PDF seconds apart,” they said. “Workday audit logs show dozens of ‘Print’ events from two IPs from a MAC which I do not use,” they added, referring to a MAC address, a unique identifier assigned to each device on a network.

“ApproveShield knew the 60-day limit yet mined everything,” they added.

The person provided 404 Media with a screenshot which shows them receiving a wave of emails from Workday saying the PDF of their paystub is now available for download. The screenshot shows 14 emails concerning payslips, many more than the four the service was supposed to download.

As I previously covered, Argyle’s approach of having individual people give up login credentials for their employer’s corporate environments may violate U.S. hacking laws. Broadly, employees do not have the authority to share corporate login credentials. In 2013, journalist Matthew Keys was indicted, and later sentenced to two years in prison, for providing hackers with his credentials for the Tribune Company. Christopher Correa, a former executive for the Cardinals, was sentenced to four years in prison for logging into a system owned by his former employer.

The renter 404 Media spoke to said the same “credential-harvesting model now dominates Georgia rentals.” They pointed to other companies such as PayScore, Nova Credit (whose leadership includes an Argyle co-founder), and Snappt which also uses Argyle.

Realistically, if a potential tenant doesn’t give up their login credentials, they won’t be able to rent the apartment. “Opt-out means no housing,” the person said.

Neither ApproveShield nor Argyle responded to a request for comment.

Hi! My book Lessons in Magic and Disaster has been out for a month, and I’ve been blown away by the response so far. So many people have told me that my fantastical mother-daughter story has made them cry or spoken to something in their own lives. I loved this review in Cannonball Read, where Emmalita calls Lessons “an achingly beautiful book” and talks about how personal her response to it has been. You can order Lessons everywhere! You can get a signed/personalized/doodled copy at Green Apple.

This Saturday, I’m going to be at Marin MOCA for Feminist Futurism vs. Project 2025 with Angela Dalton, Faith Adiele, Tamika Thompson and moderator Isis Asare.

Next Weds 10/1, I’ll be at Pegasus Books for Bay Area Sci-Fi Wizards, with Sarah Gailey, Susanna Kwan, Annalee Newitz and Lio Min.

On Thurs 10/2, I’ll be at Cafe Suspiro for the Stir reading series.

I keep trying to make sense of our violent times

Violence has been a major theme in my work ever since, well, 9/11. In the aftermath of those attacks, I saw people driving themselves into a frenzy of violent retribution, and the marshaling of groupthink towards driving us into two foolhardy wars, and I felt like I needed to find some way to speak to this moment.

Nearly twenty-five years later, I'm still trying to find ways of talking about our love of violence as a species — and our obsession with using force to control people and reinforce our beloved hierarchies.

After 9/11

So yeah, I was freaked out and furiously angry in 2002-2003, watching all the militaristic posturing and the disingenuous drumbeat to war. I needed to find a way to talk about it.

At that time, I was also obsessed with writing comedy, including a lot of gonzo physical comedy. I loved watching characters try to maintain their dignity and sense of reality while slipping and sliding, knocking over everything in their path, careening toward chaos.

And I remembered something my dad used to say: he couldn't watch a Charlie Chaplin movie when he was a kid, because he found Chaplin’s brand of slapstick too sadistic. He felt like a lot of slapstick comedy, such as the Three Stooges, involves a certain amount of violence that is played for laughs because you are laughing at the person on the receiving end. (See also “splatstick,” where gory body horror is played for laughs, e.g. Dead/Alive.)

So that led to my novella Rock Manning Goes for Broke, which I started writing as a novel sometime in 2002. The story of a slapstick performer who gets swept up in a fascist takeover of the United States, Rock Manning felt like the perfect way to explore the intersection of slapstick comedy and real life violence, and the ways in which we can witness horrible atrocities being done to people as long as we can either laugh or dissociate ourselves from empathizing with them some other way.

The Society for Ethical Violence

In the novel-length version of Rock Manning, there’s an organization called the Society for Ethical Violence — a group of progressives who argue in favor of using violence to make the world a better place. They claim to hate violence, but have decided that it’s impossible to avoid because it’s part of human nature and therefore ought to be harnessed for good. The leader of the Society for Ethical Violence is a charismatic older white guy named Guthrie Hirsch who rose to fame as the next Howard Zinn.

In this version of the story, Rock has a girlfriend named Carrie who falls into Guthrie’s orbit. And Rock is almost sucked in as well:

Carrie said it all made sense when Guthrie talked, and he could look straight into you and see not just the hurting part, but the part that wanted to hurt others. He could make you feel safe from yourself. What had happened to Guthrie during that year or so he was missing, nobody knew, but he'd come back ten years older and with twice as much energy.

The leaflet showed him, eyes glowing, long gray beard with no mustache, one leather fist up. It said our potential for physical aggression was the engine that built civilization, which then turned around and tried to repress that potential, and that's why civilizations fail. So we could save our civilization if we reclaimed our love of violence. …

"We talk about the social contract," Guthrie Hirsch said when I met him a few days later, "but people forget, all contracts are enforced. Meaning, we use the threat of force to make people honor them." Blah blah blah. It was like being back at school, except we were outdoors and there was no desk for me to set on fire by accident.

I was sad to lose Guthrie Hirsch when I turned Rock Manning into a novella, but for various reasons neither he nor Carrie quite fit anymore. And I’m glad I revised Rock Manning and was able to release it at last, because its depictions of fascism were becoming more and more relevant.

Still, that stuff about “contracts are enforced” feels like it’s laying down a theme that’s come up in my work ever since: violence is baked into all of our systems and we are so used to it that we’ve stopped seeing it. A couple of other more recent examples feel especially relevant just about now.

My novel The City in the Middle of the Night includes a character named Mouth who is a self-proclaimed bruiser. In fact, I make a huge point of showing from early on how Mouth’s internal monologue classes with the story she tells about herself. In her very first chapter, she's boasting about taking down a group of thugs who tried to rip off her smuggler crew, but meanwhile her inner monologue is endlessly worrying about whether all of that killing had really been necessary and whether she could justify ending those lives. Mouth comes from a spiritual background, and has never fully accepted the kill-or-be-killed ethos of the smugglers she’s joined.

Later in the book, Mouth has a kind of breakdown, and finds that she can no longer do violence. She freezes up when she reaches for a weapon or tries to make a fist. She still wants to protect her beloved Alyssa, but has to find ways to do it without hurting anyone. The dilemma of being thrust into violent situations without being able to commit violence felt really interesting to me, but so did the visceral disgust towards violence and the self-loathing that comes with it, which force Mouth to become a pacifist.

I basically explored the same notion a second time in my young adult books. (It’s only hitting me now just how much I was exploring some of the same territory in a different way.)

Victories Greater than Death is about a teenager named Tina, who is secretly a clone of the galaxy's greatest hero, Captain Argentian. Tina is supposed to get all of Captain Argentian's memories, but the process fails and she's left with only the Captain’s skills and knowledge. Tina is desperate to prove that she can live up to the legacy of this legendary hero, and that longing powers the entire first book of the trilogy.

When I was writing Victories Greater than Death, I had a pretty solid outline that involved a lot of space battles and fighting. Somewhere in the middle, I decided to write a bunch of short little adventures that Tina and the rest of her starship crew could go on, so Tina could bond with her shipmates and get some experience. When I was writing a bunch of those little vignettes, I wrote one scene where Tina kills some bad guys for the first time — and I hadn't consciously anticipated what that would be like.

The process of ending someone's life — watching them transform in real time from a person with opinions and ideas and joys and pain to just nothing — is overwhelming. Tina goes into a tailspin, and by the end of the first book, Tina has reached a decision: she vows never to take a life again. Needless to say, this was one of the things that torpedoed my carefully laid plans for the second and third books of the trilogy.

But it also opened up a lot of interesting story lines that I hadn't expected. The third book of the trilogy, Promises Stronger than Darkness, culminates in a huge dilemma: do we kill a few thousand morally compromised people to save the galaxy? Tina just forced to wrestle with this choice, and — spoiler alert! — only figures out another alternative at the last possible moment.

What I believe

Writing these books definitely forced me to think a lot about where I stand with regard to violence. I have a deep and visceral revulsion toward the notion of committing violence, and I sure as heck don't want to be on the receiving end of it. I'm not sure that I'm an absolute pacifist — if I were under attack by genocidal maniacs or invading imperialists, I might not have any choice but to take up arms. My objections are at least in part emotional rather than moral.

But I do believe that violence is disgusting and shameful. Sometimes you have to do revolting things to survive, but you don't brag about them or glorify them, and you try like hell to avoid doing them. That's my baseline belief, I think.

Coming back to what Guthrie Hirsch says about the social contract, I also think that there are a lot of things that we don't consider violence, which are actually quite violent.

Probably the most the second most quoted line in The City in the Middle of the Night is when Mouth says:

Part of how they make you obey is by making obedience seem peaceful, while resistance is violent. But really, either choice is about violence, one way or another.

Combine that with what Guthrie Hirsch says about the social contract, and that sums up a lot of stuff.

Society runs on violence, and no aspect of society can function without it. Taxation is the government taking your wealth from you by force, with the threat of imprisonment if you fail to comply. Most of us are aware on some level that there are forms of behavior that are intrinsically harmless to others, but which will expose us to the to a high risk of violence if we engage in them. Until recently, being openly trans was punishable by violence almost everywhere, and it still is in many situations.

Lessons in Magic and Disaster isn’t as explicitly about violence, but my protagonist Jamie has an epiphany in the latter part of the book, that she’s been committing a kind of violence against her partner Ro by trapping them in a story they didn’t choose. Jamie reflects:

If forced imprisonment is a form of harm, then trapping someone in a toxic narrative could be considered an actual assault.

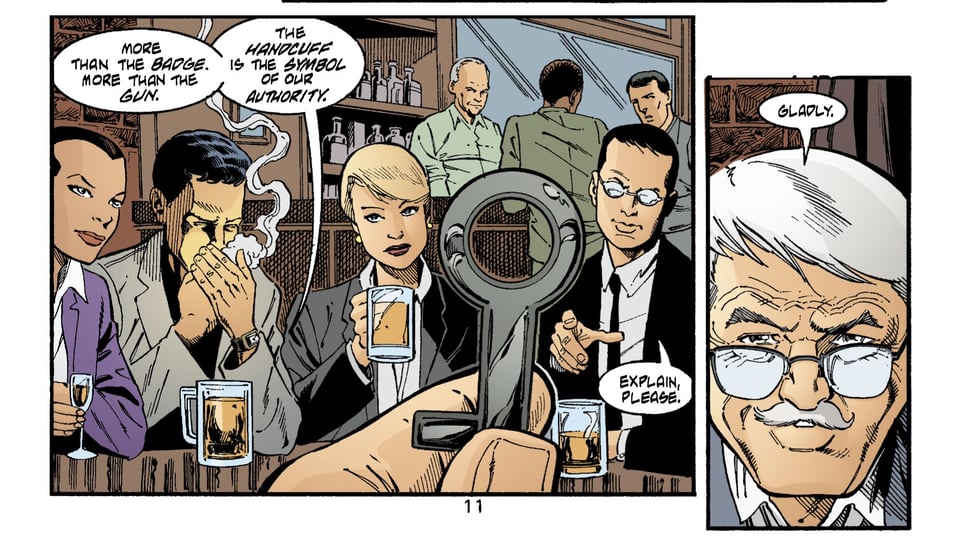

I think often about Batman #587, written by the always essential Greg Rucka with art by Rick Burchett and Rodney Ramos. The cops throw Commissioner Gordon a birthday party and he rewards them with a lecture about why handcuffs are the ultimate symbol of police power:

Gordon goes on to say, “We are the only people in this free nation who have the power to deprive a citizen of their freedom. Of their liberty. The only people with the authority to hold them against their will.” The power of arrest is the most awesome weapon in a cop’s arsenal, even more than a gun.

When people decry the horribleness of political violence, what they're really saying is that they want those who have been designated by the state to have a monopoly on the use of violence. Or perhaps, that those who have been committing violence with impunity for decades should continue to have a monopoly on it.

So… I'm super interested in questioning the necessity and usefulness of violence — when is it justified to fight back?

But I'm also increasingly interested in exploring how violence is embedded in every part of our world, from law enforcement to the sheer brutality of late stage capitalism. And the extent to which we pretend that we're not participating in violence when we clearly are, but we also treat certain kinds of violence as natural and praiseworthy.

We are all the Punisher

Lately, I keep thinking about that punishment is such a huge part of our worldview — to the point where many religions include some aspect of supernatural punishment for wrong actions. Either reincarnation into a form that causes suffering, or unending torture in a cosmic barbecue pit. When people say that they don't believe you can be a good person if you do not believe in God, I feel as though they are really saying that they don't believe people will behave decently without the threat of punishment.

It's not just that we encourage people in uniform to mete out brutality on our behalf. It's not just that we know on some level that our whole economy is built on mistreating people. It's also that deep down, we believe that all good behavior comes from the existence of a supernatural torture chamber. This is the backdrop against which we ask ourselves if violence can be justified. Until we’re honest about how much our culture sees violence and punishment as essential and beneficial, then our conversations about violence will always be carried on at the level of peevish little children.

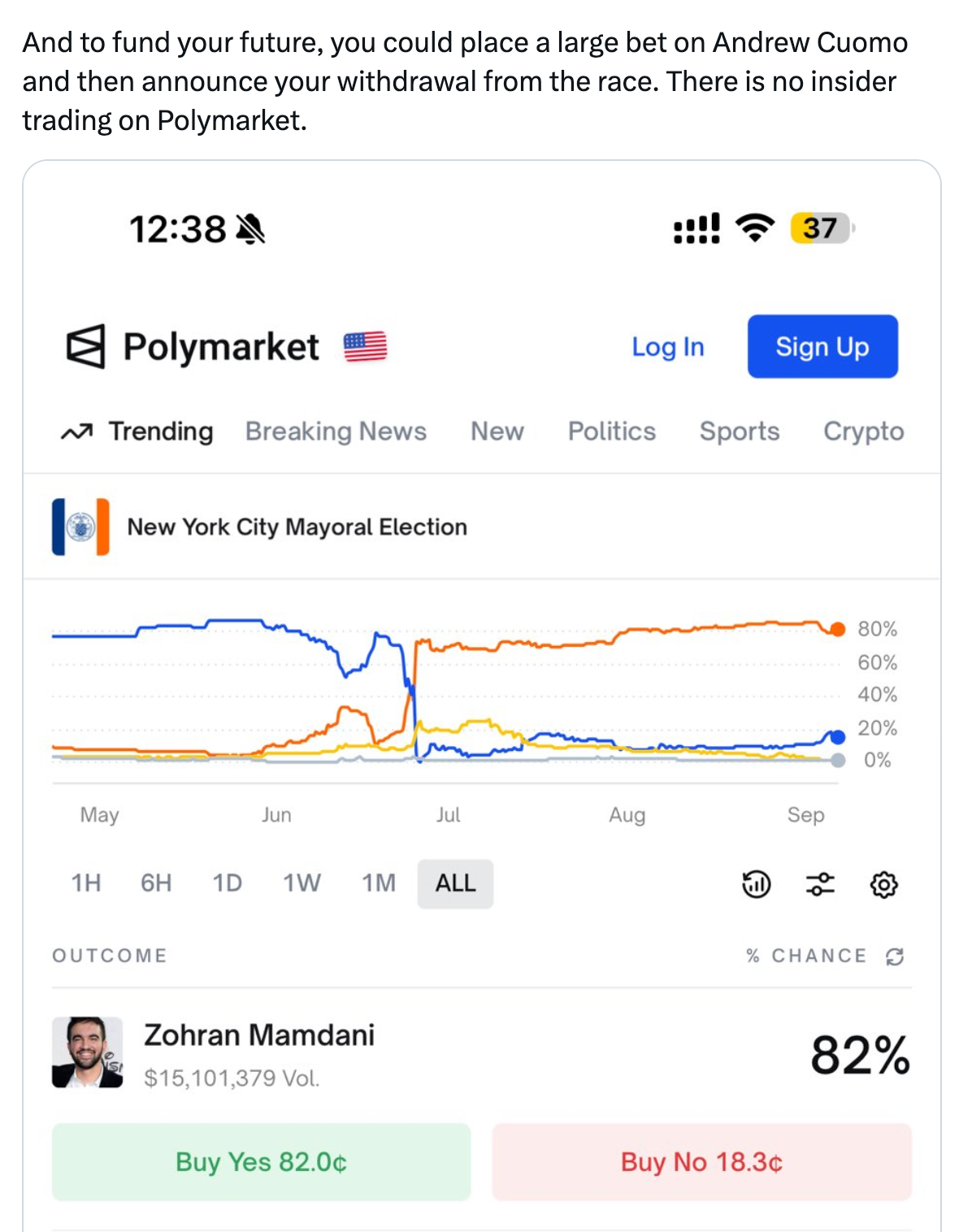

When billionaire Bill Ackman suggested on Twitter that Eric Adams could “place a large [Polymarket] bet on Andrew Cuomo and then announce [his] withdrawal” from the New York City mayoral race, he described something that feels profoundly illegal. A politician profiting from non-public knowledge of their own withdrawal from an election surely crosses some line — insider trading? Market manipulation? Election interference? Illegal gambling? Ackman ended his tweet: “There is no insider trading on Polymarket”1 — not because it doesn’t happen, but because it won’t be charged. He’s right: the Securities and Exchange Commission’s insider trading rules don’t apply here. But that leaves the question: what rules, if any, do?

As Ackman says, prediction markets fall outside the SEC’s jurisdiction,a living in a different regulatory world than stock markets where executives get prosecuted for trading on non-public earnings or tipping off friends about upcoming mergers. Unlike crypto’s ongoing turf wars between regulators, prediction markets have a clear home: the Commodity Futures Trading Commission, which oversees futures, swaps, and other derivatives trading. A farmer worried about a poor wheat harvest can buy futures contracts that rise in value if wheat prices increase, helping to offset the money lost from selling less grain. An airline can buy oil-based futures contracts to offset the risk of jet fuel costs rising, effectively letting them budget fuel at today’s prices even if market rates climb before delivery. Some derivatives markets more closely resemble prediction markets, dealing in events rather than commodities — for instance, ski resorts can hedge against poor snowfall by trading weather-based contracts.

While farmers hedging wheat prices serves a clear economic purpose, prediction markets operate in murkier territory. When people trade on sports games or celebrity relationships, are they engaging in legitimate derivatives trading deserving the same regulatory treatment? Or are platforms like Kalshi and Polymarket essentially gambling sites operating under the veneer of financial markets? And with participants potentially losing big money to better-informed insiders, who’s ensuring these markets stay fair? What happens when prediction markets collide with other issues — from market manipulation to gambling addiction to election integrity?

Citation Needed is an independent publication, entirely supported by readers like you. Consider signing up for a free or pay-what-you-want subscription.

The history of prediction markets

Prediction markets — platforms where people trade contracts that pay out based on whether specific events happen — have enjoyed a surge in popularity over the last few years as they’ve dramatically expanded their operations in the United States. While they have existed for decades, they were long confined to strictly academic exercises — operating as small-scale non-profits that carefully constrained their operations to avoid running afoul of the CFTC. The pioneers were university-affiliated non-profits like Iowa Electronic Markets, which capped trades at modest dollar amounts, and later PredictIt, which followed a similar model. The CFTC allowed their elections- and economy-related markets by issuing no-action letters, recognizing there was value in studying whether crowdsourcing predictions through financial markets could outperform traditional polling and forecasting methods.

In 2020, the US-based Polymarket began allowing customers to use cryptocurrency to trade events contracts, though they made no effort to certify their contracts with the CFTC. In 2021, Kalshi emerged as the first fully regulated prediction market in the US, following a hard-won CFTC approval. That platform allowed traders to stake up to $25,000 on outcomes ranging from COVID-19 vaccination rates to record-breaking temperatures.

The CFTC cracked down on prediction markets in 2022. First, they hit the unregistered Polymarket with a $1.4 million fine and ordered it to stop offering unregistered event contracts to US customers, effectively shutting the platform out of the American market.2 Then they revoked PredictIt’s no-action letter,3 apparently concluding the platform had expanded beyond its academic purpose into a commercial enterprise. PredictIt challenged this decision in court, winning a preliminary victory in 2023 and a final one in 2025. In 2023, the CFTC ordered Kalshi to stop offering markets on which party would control Congress after the upcoming elections, citing the Commodity Exchange Act’s prohibition on “gaming”. Kalshi also mounted an aggressive legal challenge, and when a district court ruled in Kalshi’s favor in 2024, the company swiftly reinstated the contested markets [I66].

The regulatory landscape shifted further after Trump took office. The CFTC’s interim leadership began championing prediction markets as “an important new frontier”,4 and dropped both their appeal in the Kalshi case and an ongoing investigation into Polymarket’s continued accessibility to US users [I89]. Polymarket acquired a CFTC-regulated derivatives exchange, and a no-action letter from the agency greenlighted their re-entry into the US [I92]. With the administration’s deregulatory stance and a nominee for CFTC Chair who sits on Kalshi’s board [I90], this permissive approach is likely to accelerate in the coming years. More companies are eager to join the fray, with Crypto.com, Robinhood, and even the sports betting company FanDuel adding event contracts to their offerings. Eyeing this lucrative market, they’re likely to follow their predecessors’ lead in pushing regulatory boundaries even if it means expensive litigation. Following the crypto industry playbook, they may also lobby Congress for special exemptions.

The regulatory landscape

The US financial regulatory landscape is divided among several agencies, with the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) overseeing stock markets and various other securities. The SEC aggressively pursues unlawful insider trading cases when people trade securities based on material non-public information. Former SEC official John Reed Stark explains, “The rationale for policing unlawful insider trading is that for the markets to work efficiently and fairly, everyone needs to be working with the same basic information, or at least, that those with special access to nonpublic information are prevented from taking advantage of it before other investors.”

But with the Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC), which oversees prediction markets, it’s a different world. Trading based on non-public information is built into the system: a cattle rancher can use early calving data to hedge against future beef prices, even though others lack access to that information. Laurian Cristea, a lawyer specializing in financial services and CFTC exchanges, explains, “it’s not wrong to trade on information you properly know or developed through your business.” Nevertheless, rules against fraud or market manipulation still prohibit trading based on illegally acquired private information, or making false or misleading statements that impact markets, and CFTC-regulated exchanges like Kalshi are required to establish and enforce their own rules to maintain fair markets.

Some states and tribal governments have also brought cases against Kalshi under state or federal gambling laws, arguing that it is skirting licensing, tax, and consumer protection requirements that apply to sportsbooks and casinos. In court filings, Kalshi insists it’s not a casino or sportsbook but rather a venue for traders to engage in “legitimate hedging”, similar to how farmers and airlines use futures markets to manage risk. However, their public messaging tells a different story, with their advertising and social media regularly inviting customers to come “bet”.

When fighting the CFTC in court over their election-related markets in early 2024, Kalshi insisted that Congress’s “gaming” restrictions were aimed specifically at sports betting, not election predictions. Their lawyers argued, “‘sporting events such as the Super Bowl, the Kentucky Derby, and Masters Golf Tournament’ were precisely what Congress had in mind as ‘gaming’ contracts”.5 A year later, Kalshi launched markets on these very same sporting events.

Kalshi has since argued they can’t be classified as a gambling platform since traders bet against each other rather than against a “house”. Andrew Kim, a lawyer specializing in gaming law and contributor to the Event Horizon newsletter, acknowledges that some of Kalshi’s arguments against state gambling oversight may be valid under a strict reading of the law, but that this particular defense is weak. “There are a number of exchange wagering outlets... generally covered by state level gambling law.” He adds: “if you play poker, the house takes a rake, but it doesn’t participate. That’s still gambling.”

Kalshi has also argued that, as a CFTC-regulated Designated Contract Market, the Commodity Exchange Act gives the agency exclusive jurisdiction over its event contracts. This claim of federal preemption has been disputed by state gambling regulators, and courts have not yet resolved the question.

Old rules, new markets

Though prediction markets aren’t a new phenomenon, their growing accessibility to retail traders is. Unlike the SEC, which prioritizes protecting retail investors, the CFTC’s mandate is centered on market integrity and preventing fraud or manipulation — not on consumer protection. Its regulations were designed for businesses hedging wheat and oil, not retail traders betting on album releases and how many times Elon Musk tweets in a month. Is a regulatory framework designed for commercial hedgers adequate for these retail-heavy markets? Should regulators try to protect retail traders who are consistently outmaneuvered by insiders with private information or other participants with structural advantages?

Some experts think the CFTC’s oversight could work. Lee Reiners, a lecturing fellow at the Duke Financial Economics Center, explains that “any insider trading on these contracts would clearly implicate the anti-fraud provisions of the Commodity Exchange Act,” potentially triggering both CFTC enforcement action and a referral for criminal charges from the Department of Justice.

When I asked Cristea about the CFTC’s ability to oversee retail markets, he pointed to the CFTC’s track record regulating Futures Commission Merchants (FCMs), which facilitate trading of futures and derivatives. While institutional clients still dominate these markets, retail participation has grown significantly in recent years. However, he notes a key difference in consumer protections: “FCMs don’t have the same sort of requirement for a customer suitability analysis that applies to broker-dealers in the securities context.” Broker-dealers are obligated to assess whether specific investments are appropriate for specific customers. For example, if a 65-year-old retiree with limited savings tried to make a substantial investment in a high-risk stock, a broker-dealer would need to evaluate whether the investment suited her financial situation and could refuse inappropriate trades.

Cristea also expressed concerns about enforcement capacity. “The current administration takes a more free market, caveat emptor-type approach. That said, even when the CFTC got jurisdiction over a very large swaps market the agency’s budget was not increased much. And together with this deregulatory trend, agencies getting smaller in size, where agencies are being told to do more with less, I am not sure the CFTC will necessarily come out with [additional retail] protections unless the agency sees that as a necessary step for credibility and for the market to thrive.” The CFTC has yet to bring any enforcement actions pertaining to market manipulation on events contracts, and it’s not clear they have much appetite to begin doing so.

Other industries that deal with outcome-based bets, like sports wagering, have evolved robust integrity systems both to protect consumers and to preserve trust in the games themselves. Kim explains, “The reason for [these rules] is because of the mob, because of the history of gambling and the mob fixing matches. You have a rather sketchy history of criminal influence on the outcome of matches, and so you want to prevent that by just having very strict rules, like if you’re involved in the event, you can’t play, period.”

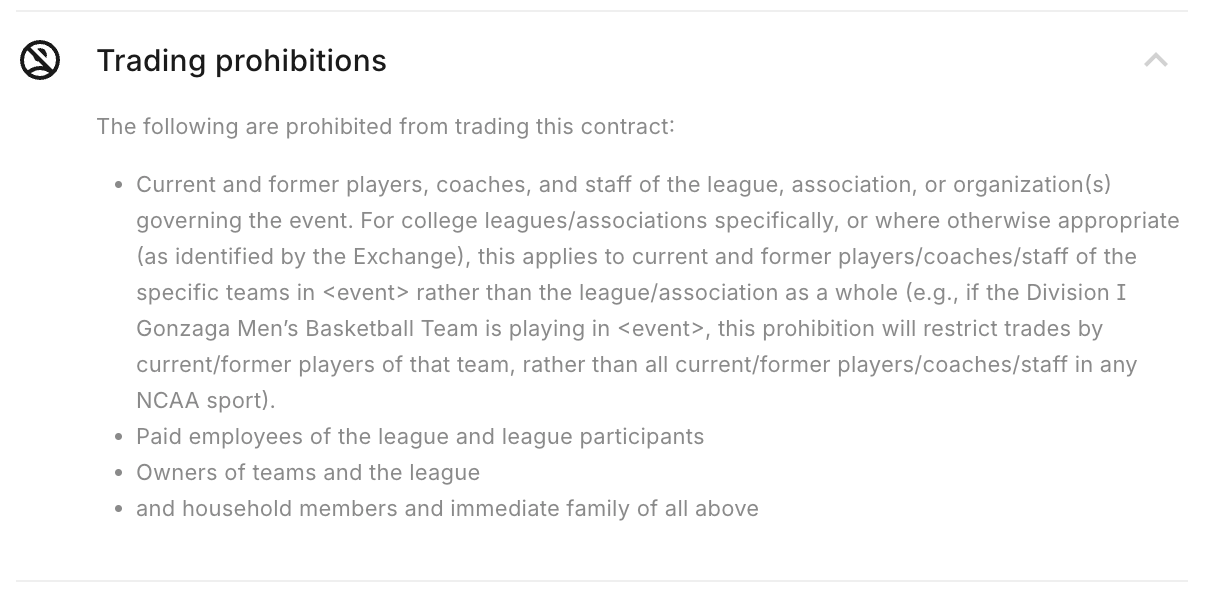

Today, sports betting platforms work to screen out athletes, referees, and sports program employees to ensure they’re not betting on games they could potentially influence, and employ monitoring programs to detect suspicious bets. This vigilance has proven effective: recent scandals involving illegal betting by Iowa State football staff and the University of Alabama’s baseball coach were first flagged by the platforms’ monitoring systems. Their vigilance is likely because, as Kim says, “the penalties for the operator can be severe. It might be a fine. It might be the license getting pulled.”

Kalshi imposes similar prohibitions on its sports-related markets, using the same IC360 platform that’s used by betting platforms like Caesars Sportsbook. Kim says he doesn’t believe this type of monitoring is something the CFTC explicitly requires of prediction markets. Cristea agreed that it may not be specifically mandated, but noted that CFTC-regulated prediction platforms must demonstrate they can effectively police their markets against manipulation. For Kalshi, implementing monitoring systems like IC360 likely helps prove to the CFTC they’re upholding their licensing obligations.

While Kalshi imposes strict trading restrictions on its presidential election market — barring politicians, campaign staff, pollsters, election officials, and foreign nationals — many of its other markets lack any such prohibitions. This includes election-related markets identical to the type of bet Ackman suggested Adams could place on Polymarket about his own mayoral campaign withdrawal.

Polymarket, which does not yet serve US customers, does no such screening. The platform merely asks users to self-certify they aren’t US-based, with additional basic geofencing that users regularly circumvent. Polymarket doesn’t require any additional identity verification, and its cryptocurrency-based trading allows users to remain largely anonymous. It remains to be seen whether, and how, the platform will implement more rigorous screening as it looks to re-enter the US — potentially alienating a crypto-native user base often resistant to identity verification requirements.

With markets on such a wide range of events, these platforms can intersect with multiple regulatory frameworks: gambling law, securities regulations, and election integrity rules. Election markets in particular have sparked intense debate, with the CFTC initially opposing them outright. When moving to prohibit Kalshi’s Congress-related markets, then-Chairman Rostin Behnam argued they would force the agency to become an “election cop”. This would mean “monitoring elections, candidates, and countless participants in the political machinations that proliferate in the media and cyberspace in an effort to prevent manipulation and false reporting within the political system” — a role Behnam said the CFTC “currently lacks the mandate to do.”6 But after losing its court battle with Kalshi, the agency had little choice but to allow these markets, and Kalshi has since dramatically expanded its election-related offerings.

The stakes of prediction markets

Platforms like Polymarket and Kalshi have already grown far beyond niche experiments, sometimes reporting over a billion dollars in monthly trading volume with hundreds of thousands of active traders. Regulators and lawmakers now face questions: Should these platforms face the same oversight as gambling operations? What obligations do they have to protect vulnerable users from addiction and financial harm? And can CFTC oversight alone prevent market manipulation and other misconduct?

The gambling question has become particularly contentious when it comes to sports markets, which dominate trading activity on prediction platforms like Kalshi.7 State regulators have argued these offerings violate state-level gambling laws, with Massachusetts being the most recent to file a lawsuit against Kalshi on September 12. In a statement, Attorney General Andrea Joy Campbell stressed, “sports wagering comes with significant risk of addiction and financial loss and must be strictly regulated to mitigate public health consequences.”8

State gambling laws vary but typically require operators to pay special taxes, implement rigorous age and location verification, and establish addiction prevention programs. While Kalshi prohibits users under 18, this falls short of some state requirements — Massachusetts, for instance, sets the minimum age for sports betting at 21. And though Kalshi offers voluntary self-exclusion for problem gamblers, they lack the automated safeguards required by some states, such as notifications or even forced cooling-off periods when users show signs of addictive behavior like rapid deposits or erratic bets.

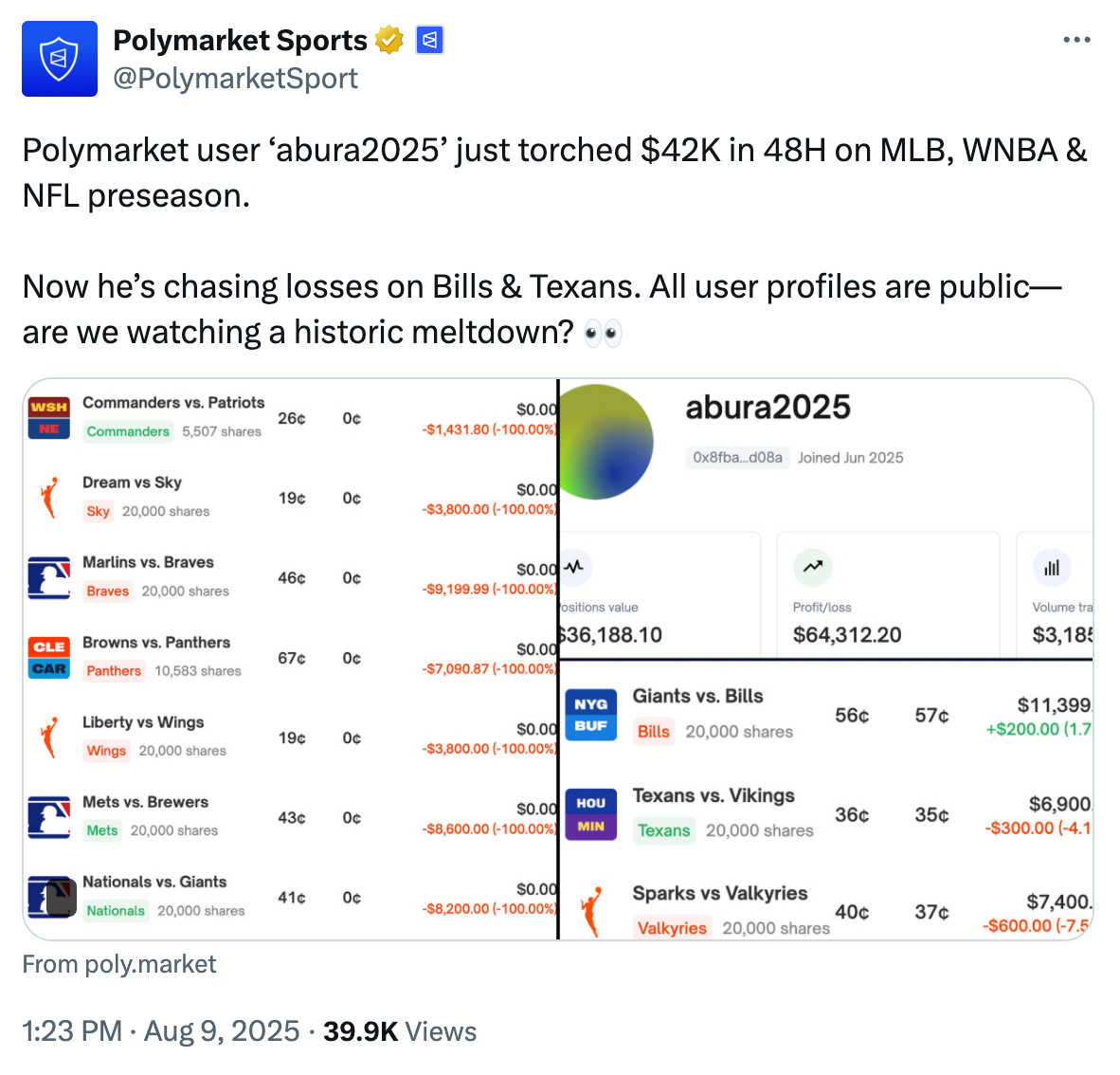

Platforms like Polymarket have even fewer restrictions. Without identity verification requirements, anyone with access to cryptocurrency can trade, including minors. The platform lacks even basic voluntary self-exclusion options, let alone more proactive safeguards. And problem gambling experts have called out the platform’s troubling attitude toward addiction.9 In one incident, an official Polymarket Twitter account highlighted a trader who had lost more than $40,000 on sports bets over two days, and publicly ridiculed them: “Now he’s chasing losses on Bills & Texans. ... Are we watching a historic meltdown?”

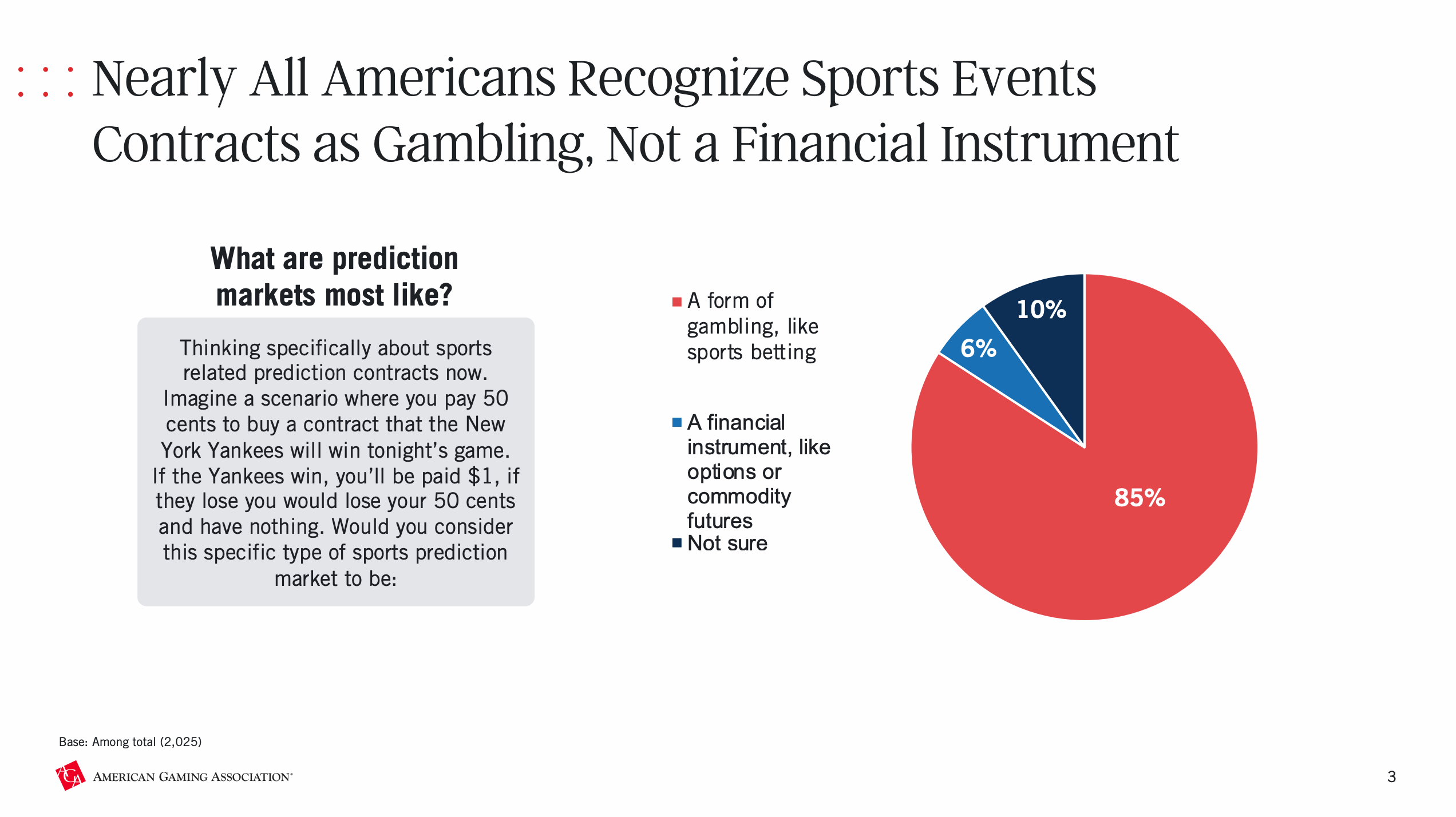

These platforms maintain that they offer financial services that shouldn’t be considered wagers. But are they really so different? “Pragmatically, I think for the retail individual, they don’t see a difference,” says Kim. “I think retail individuals trading on these platforms are not thinking of it as not gambling. They’re just thinking of it as one more outlet for them to participate in the opportunity to put money on an event.” Recent research supports this, with a study from the American Gaming Association finding that most Americans view sports-related prediction markets as a form of gambling.10 But at the same time, Kim sees some legitimate arguments from these platforms that they are offering swaps and not wagers, at least when it comes to a strict reading of the law.

I posed the same question to Cristea. “What’s the difference between gambling and trading? The difference is likely whether certain activity is done on a federally-regulated market, like a CFTC or SEC registered exchange.” He acknowledged that, particularly for unsophisticated investors, the line between gambling and trading can be blurry regardless of where they’re placing their bets or trades. “If you have a gambling addiction, could you satisfy it by going and trading an oil future or a gas contract or a Microsoft stock? Maybe. ... I mean, there are people who are day trading, right? And if you talk to anybody about day trading, especially people who work in finance, they will likely say, ‘oh no, I invest in ETFs, money market or mutual funds. Day trading is like gambling all the way.’”

When Kalshi self-certifies each contract to the CFTC, it attests that these markets serve a legitimate economic purpose, such as hedging, price discovery, or risk management. But many of its offerings have no plausible connection to those functions. Sure, there are probably more sports fans recreationally placing trades on who’s going to make it to the later rounds of March Madness, but one could argue that a bar operator might theoretically use these markets to hedge against uncertain revenue if their local team fails to advance. But this kind of rationale is harder to find across many of Kalshi’s other contracts, such as who will serve as a bridesmaid at the wedding of Travis Kelce and Taylor Swift, or whether a popular YouTuber will cut his hair on stream. Polymarket, which does not yet answer to the CFTC, has even more egregious examples: Will Hailey Bieber get pregnant this year? Will the Obamas divorce? Will Trump say the word “pizza” in September? These markets seem far removed from the original purpose of futures trading — under the Commodity Exchange Act, the justification for letting futures markets exist outside gambling law has always been that they serve an economic function by giving commercial actors tools to manage risk.

Election integrity presents another major concern, as prediction markets create new financial incentives that some fear could (further) distort democratic processes. When defending its ban on Kalshi’s Congressional contracts in court, the CFTC found support from consumer rights advocacy groups like Public Citizen, whose Lisa Gilbert warned that “layering in gambling on our elections will take our democracy in precisely the wrong direction.”11 In an amicus brief, the financial reform group Better Markets argued these markets threaten both investors and democratic institutions.12 “Evidence is fast emerging that these types of election wagering contracts may already be serving as instrumentalities of either election manipulation for political gain, market manipulation for financial gain, or both,” they wrote, citing a Wall Street Journal article suggesting that Polymarket traders might have been artificially pumping up contract prices on a Trump election victory.13

Going back to Ackman’s idea: directly paying a candidate to drop out of a race is likely illegal, but it’s not clear if laws aimed at maintaining election integrity could be applied to prediction markets. Public Citizen’s government ethics expert Craig Holman is skeptical. “I do not see how that type of unethical election gambling would be illegal, even if you could prove deceptive intent,” he explains.

Finally, there’s the question of whether the CFTC is equipped to handle these surging markets, and the demographic they attract. Unlike state gambling commissions, the CFTC’s primary focus is on fraud and market integrity, not addiction or financial harm to amateur traders. Will it need to expand its mandate to address these consumer protection issues, or will some other regulator need to step in? Cristea says there isn’t a clear right answer. “Maybe there does need to be some sort of retail protection in there.”

Stark offers a different possibility: “I just don’t know if anyone cares if the Polymarket marketplace is completely corrupt — that is the sole reason to police that sort of conduct. If uninformed participants don’t care that betting in Polymarket becomes like betting on a World Wrestling championship match outcome, then regulators won’t care either.”

Unanswered questions

When Bill Ackman casually suggested Eric Adams could “fund his future” by betting on his own withdrawal from the mayoral race, he inadvertently highlighted some of the thorny questions around prediction markets. The industry’s growth under Trump’s deregulatory agenda is likely just beginning, and more companies are entering the space — from crypto exchanges to gambling platforms. Some will probably follow Kalshi’s playbook of aggressive litigation to expand the range of permissible contracts. Others may copy Polymarket’s approach of trying to skirt regulatory authority with crypto-denominated trades. Some gambling platforms may attempt a version of regulatory arbitrage, particularly if the outcomes of ongoing court cases suggest that such companies can dodge heavy taxes and onerous compliance burdens by reinventing themselves as trading platforms.

Without much oversight, these markets are ripe for manipulation. The gambling-like nature of many markets, combined with limited addiction prevention programs, likely puts vulnerable users at risk. And election markets create concerning new financial incentives that could further corrupt democratic processes.

Can the CFTC, traditionally focused on institutional traders and commercial hedgers, effectively oversee retail-heavy prediction markets? Should these platforms face the same strict integrity requirements as sportsbooks, barring insiders from trading on events they can influence? Should betting on political outcomes be allowed, or will it inevitably create perverse incentives that could undermine democracy? What types of events should be eligible for trading? Weather events and inflation rates might seem relatively uncontroversial, but what about contracts that could incentivize harmful real-world actions? And how should regulators balance consumer protection against personal responsibility when it comes to retail traders who may be, essentially, gambling beyond their means?

With prediction markets already handling billions of dollars in trades and more platforms launching every month, regulators need to grapple with these questions before the industry grows too big to effectively control. The cryptocurrency industry has shown how difficult it becomes to implement meaningful oversight once a poorly regulated industry accumulates enough money and political influence to push back — and the devastating cost to everyday people who get caught in the fallout.

Have information? Send tips (no PR) to molly0xfff.07 on Signal or molly@mollywhite.net (PGP).

I have disclosures for my work and writing pertaining to cryptocurrencies.

Footnotes

With the caveat that the SEC could theoretically bring a case if they decided these markets were influencing securities markets. ↩

References

“CFTC Orders Event-Based Binary Options Markets Operator to Pay $1.4 Million Penalty”, CFTC. ↩

“CFTC Staff Withdraws No-Action Letter to Victoria University of Wellington, New Zealand Regarding a Not-For-Profit Market for Certain Event Contracts”, CFTC. ↩

Motion for summary judgment filed on January 25, 2024. Document #17 in KalshiEx LLC v. CFTC. ↩

“Statement of Chairman Rostin Behnam Regarding CFTC Order to Prohibit Kalshi Political Control Derivatives Contracts”, CFTC. ↩

“Kalshi Trading Volume Soars As Football Betting Season Kicks Off”, LegalSportsReport. ↩

“AG Campbell Sues Online Prediction Market for Illegal and Unsafe Sports Wagering Operations”, Office of the Attorney General for Massachusetts. ↩

“Polymarket Publicly Shames Person Showing Signs Of Problem Gambling”, Gambling Harm. ↩

“Sports Event Contracts: Public Opinion Landscape”, American Gaming Association. ↩

“CFTC Must Reject Dangerous Election Gambling Proposal”, Public Citizen. ↩

Amicus brief by Better Markets, filed on October 23, 2024. Document #2081637 in KalshiEx LLC v. CFTC. ↩

“A Mystery $30 Million Wave of Pro-Trump Bets Has Moved a Popular Prediction Market”, The Wall Street Journal. ↩